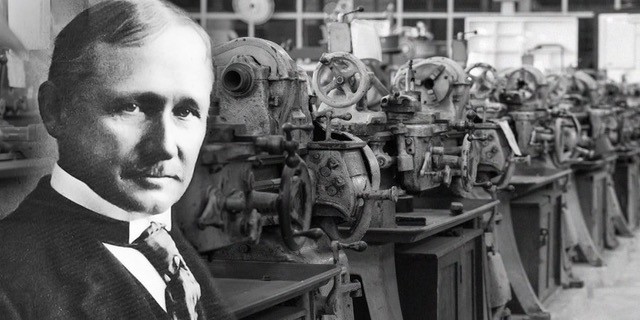

Frederick Winslow Taylor shaped the field of management science. He believed systematic and scientific methods could be applied to managing operations and production. His work inspired the formation of the Harvard Business School and the modern assembly line. The Academy of Management named his Principles of Scientific Management as one of the 20th century’s most influential books.

Over a hundred years later, Taylorism still casts a shadow over management theory. Many of his principles are so deeply embedded that they are almost mistaken as laws of nature. Others have been discarded as irrelevant, ineffective, or counter-productive.

It is insightful to understand Taylorism in its historical context. Life in 1900 was very different from today. Farming was still the primary occupation. Few adults (13%) earned high school degrees, and even fewer (3%) graduated from college. Manufacturing was still dominated by skilled craftspeople with apprentice labor.

Taylor created the framework that enabled mass production. Complicated processes were decomposed, standardized, and made more efficient. This allowed semi-skilled laborers to replace the craftspeople.

Scientific Management

Taylor asserted the country was “suffering through inefficiency,” caused by workers deliberately “soldiering” or working slowly. The “remedy to this inefficiency lies in systematic management,” which was defined as:

- Using science, not the “rule of thumb,” to define work processes;

- Having harmony rather than discord between management and labor;

- Avoiding individualism and pacesetting; and

- Workers maximizing output rather than restricting it.

He envisioned a sweeping change in labor-management relations. The responsibility for defining work processes, setting and maintaining the pace, and training shifted from labor to management. Companies would benefit through increased output at a lower cost. Workers would benefit through higher wages; consumers would benefit through cheaper goods.

Managers would systematically review every step in the production process. Wasteful steps and unnecessary motions were eliminated. The optimum pace was established. Compensation was adjusted to incent ideal output. Experiments were used to define everything from the correct shovel size to the best mix of work and rest.

We can see Taylor’s influence on modern management practices. Toyota’s definitions of waste, are nearly identical to his. The Shewhart/Deming Cycle of plan-do-check-act is a later incarnation of his scientific process. The mantra of “doing more with less” would be music to Taylor’s ears.

While Taylor believed he benefitted workers, they complained of constant exhaustion. At his funeral, he was eulogized by industry titans; yet no one from labor even attended. Moreover, recent critiques of his work question the veracity of his reported successes.

Social & Management Thinking

Many of Taylor’s ideas were similar to other controversial pseudo-science movements of that period. Social Darwinism applied “survival of the fittest” to status—arguing that the rich and powerful were innately better. Eugenics was even more extreme, claiming that certain ethnic groups were genetically inferior. These theories have long been discredited as false and racist.

Taylor proudly cites his success at increasing the output of pig-iron haulers at Bethlehem Steel. His first step was to find the best candidate. He spent days observing different men and categorized them by their nationality and physical traits. He thought the “large powerful Hungarians” would do well, but they refused to quadruple their output. Instead, he found Schmidt, a “mentally sluggish” but happy and hard-working Dutchman.

While Taylor claimed he wanted to “secure maximum prosperity” for workers, he limited these benefits. He argued that a raise of 60% made workers “more thrifty,” “more sober,” and led to more steady work. Higher wage increases resulted in them being “shiftless,” lazy, “extravagant,” and unpredictable. These assertions are dubious and paternalistic.

Lean Process Engineering

The assembly line is a direct descendant and application of scientific management. Over a decade, Henry Ford evolved the Model-T production line to make it a paragon of efficiency. The production process was decomposed into 88 simple and repeatable steps. Management set the line’s speed to optimize output. Workers performed machinelike tasks as the cars rolled past.

The Model-T was a success! The time required to build a car fell from over 12 hours to 93 minutes and the cost dropped from $850 to $295. However, the work was tedious, the days were long, and workers started to quit. To maintain a labor supply, wages doubled to $5/day, drawing people worldwide to Detroit.

Modern process management practices are both reactions to and extensions of Taylorism. Toyota is credited as being the progenitor of Lean Management. Rather than directly competing against Ford, Toyota exploited weaknesses in its system. It employed just-in-time delivery to reduce inventory, pull to improve flow, and continuous improvement to reduce the cost of rework.

Toyota adopted a fundamentally different management philosophy based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Rather than seeing labor as just another factor of production, workers became partners in the process. They had job security, good pay, and safe working conditions. Significantly, they were valued partners in the quest to improve the process and product quality.

The roots of value stream management can be traced to Taylor’s obsession with removing process inefficiencies. They share the goal of eliminating hand-offs, extra processes, and waiting. Today we favor a more organic approach to continuous improvement over external specialists.

The negative consequences of Taylorism in the modern economy are also apparent. For example, Amazon revolutionized package delivery. However, its warehouse workers have paid the price with injuries reported at twice the industry rate. In some companies, knowledge workers’ productivity and compensation are measured based on online activity with adverse consequences.

Organizational Change

Taylor estimated adoption of scientific management practices required at least 3-5 years. Gradual education and training were needed to maintain harmony between labor and management He warned that simply applying the practices would be counterproductive. He predicted there would be strikes, the “downfall” of those leading the change, and organizations being worse off than where they started.

Nearly a century later, organizations still struggle with transformative change. John Kotter estimates that it takes 5-10 years to embed a new management approach in corporate culture. The new approaches are fragile and subject to regression, with about a third of efforts being successful. While much has changed since Taylor, the difficulty and complexity of transforming the workplace are still complex.

© 2023, Alan Zucker; Project Management Essentials, LLC

See related articles:

To learn more about our training and consulting services or subscribe to our newsletter, visit our website: http://www.pmessentials.us/.

Image courtesy of: Alex Kemp