The podcast for project managers by project managers. We’re taking a tour of the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design. This building was built to the Living Building Challenge 3.1 certification standards, the most advanced measure of sustainability possible in the current built environment. , before COVID19 quarantine restrictions.)

Table of Contents

01:45 … About The Kendeda Building

02:51 … John and Shan: Proud Parents

05:06 … Project Schedule

06:13 … The Kendeda Fund

07:49 … The Living Building Challenge: Version 3.1

10:48 … Red List Materials

12:27 … Ceiling Construction

14:46 … The Staircase Story

16:14 … Managing Triple Constraint Requirements

18:47 … Understanding the Project: John’s Story

20:16 … Team Selection Process

22:44 … A Heavily Populated Certified Living Building

24:23 … Continuing Education

26:07 … Podcasting in the Restroom

28:25 … Net Positive Water Consumption in the Bathroom

29:45 … Turning Waste into an Asset

31:07 … Podcasting in the Basement

35:58 … Project Surprises

39:15 … The Cost of Sustainable Design

40:50 … Looking Back on the project

44:34 … Closing

WENDY GROUNDS: Welcome to Manage This, the podcast by project managers, for project managers. I’m Wendy Grounds, and with me is Bill Yates. And Bill, we’re doing something very different today, it’s a first for Manage This.

BILL YATES: This is a very different episode. Wendy you’ve connected with leaders of another fascinating project, and this time we’re gonna go to the source, we’re gonna see it. So this one’s all about sustainability, and we’re going to look at a living building. Now, recently I took a tour of the Ford Rouge Factory where Ford Motor Company makes F150s, those pick-up trucks, and they build those under a huge space, and they have a roof that’s a living roof.

WENDY GROUNDS: Ahh okay.

BILL YATES: It’s 450 thousand square feet. So they’re able to capture the water, they have drought-resistant ground cover on top that collects and filters the water that they use in their manufacturing process. It’s one of the largest living roofs in the world, and

WENDY GROUNDS: Very cool

BILL YATES: I’ve seen it.

WENDY GROUNDS: Ah very nice

BILL YATES: So I can’t wait to check out this living building.

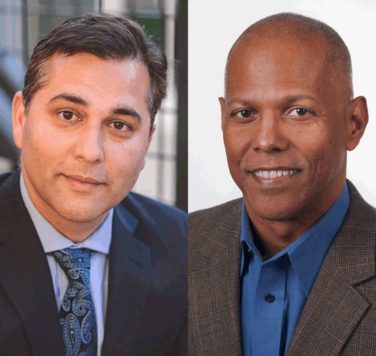

WENDY GROUNDS: I hadn’t heard about that one, so I’m excited to to where we’re going today. So the Georgia Institute of Technology constructed The Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design, and they call it a living-learning laboratory, and the two guests we’re talking to today are both working in The Kendeda Building. The first one is John DuCongé. John is a senior project manager in the design and construction department at Georgia Tech. Currently, John serves as a senior project manager on The Kendeda building. Our other guest is Shan Arora. He’s the director of The Kendeda building.

BILL YATES: Yes, so let’s take a tour of this living building here that is on the campus of Georgia Tech, and check it out.

About The Kendeda Building

BILL YATES: We are on the Georgia Tech campus. We are in a gorgeous building, and I can’t wait to dig into more about it, and John, so you’re the project manager on this. Give us a sense, help the audience understand what we’re looking at here, so tell us some of the specs on this building.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Okay, this is a 37,000-square-foot building. It’s a classroom building and auditorium, we also have class labs in the building. And it’s fully functional as an academic center on campus that’s featuring a lot of sustainable design initiatives that, you know, we as a campus have been trying to achieve, and so this is taking us to a new level of sustainable design.

Having a Living Building Challenge project on campus is really an accomplishment for us. We’re thankful to the Kendeda Fund for sponsoring this project. It is a combination of different types of construction, so we have a lot of wood in the building, but we also have a steel canopy. So it’s a hybrid of different building types. But it’s a two-story building with a basement, and it’s beautiful.

John and Shan: Proud Parents

BILL YATES: John and Shan have made a pretty good analogy about the way both of them have been involved in this building. And Shan, so you talked about you both feel like you’re proud parents, tell us more about that.

SHAN ARORA: The Living Building Challenge, well, the living part is this idea that we need to have buildings that give back more than they take, give back more to nature, give back more to people than they take from nature and take from people, so this notion is a regenerative building, a Living Building. John has been with this project for five years. I’ve been with the project for 18 months, and then Marlon Ellis, who is on the Facilities side, has been on this project for about 13 months.

Marlon and I started talking about each other as the co-parents of this building. But that’s really not accurate because John as the project manager really took the building to a certain point and then handed it off to myself and Marlon. So just now, while talking to you all, has said we’re like in an open adoption situation. John gave birth to the building, Marlon and I – we adopted the building, and so now we’re in an open adoption situation where, no matter what, John can’t get away. John is stuck with this baby forever. And that’s a unique thing about John’s role as a project manager on a Living Building.

In order to become Living Building Challenge certified, you have to prove performance, and what that requires is over the course of 12 months you have to prove that you’re net positive energy, that you’re net positive water. One of the things that the Kendeda Fund and Georgia Tech have both committed to is that we want to operate this building to net positive standards for 20 years. Once we get certified, we’re not going to go back to our old habits, we’re going to maintain net positive energy and water for 20 years.

So John’s role in this project becomes perpetual because he’s got a tremendous amount of institutional knowledge on how did we get to the point where John handed it off to me and Marlon? So while his day-to-day involvement with the building is going to decrease, he’s never going to be able to get away because he’s the birth mother.

Project Schedule

BILL YATES: Proud parents. This is great. John, just give us a quick statistic, too, on – everybody wants to know the schedule, so when did this project kick off? When did you guys break ground? And then when did you cut the ribbon and start using the building?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Okay, well, I first got involved in this project in 2015, as Shan said, and we issued the RFP for the design team at that point. We ended up with selecting the Lord Aeck Sargent / Miller Hull team as a result of that process.

And so once we got that team onboard, we also selected the contractor. One of the other key things about the way that we do things here at Georgia Tech is that we try to get the major team members involved early, so we selected the design team. We immediately followed up with getting the construction manager aboard, Skanska, and then after that the commissioning agent. So we had all of the different major parts and pieces of the team in place.

And then we went forward with design starting roughly in May of 2016. And then we went through a long process of design. And then eventually I think we started construction in February of 2018, substantial completion was achieved this past September of 2019.

The Kendeda Fund

WENDY GROUNDS: Shan, tell us a little bit about the Living Building Challenge. You’ve mentioned some Petals, if you could explain what all that is about, and also tell us about the Kendeda Fund and how the building came about with that.

SHAN ARORA: So the Kendeda Building was designed and built to something called the Living Building Challenge, version 3.1 and it’s the world’s most rigorous building certification program.

The Kendeda Fund funded 100 percent of the design and construction of the building. The Kendeda Fund is an Atlanta-based philanthropic foundation. Early last decade, Diana Blank, who is the founder of the Kendeda Fund, was on a tour of the Bullitt Center out in Seattle, so that was the first fully certified Living Building. And she said we need this in the Southeast, it’s one thing for it to be done in the Northwest, so if we can do it in the Southeast, you can do it anywhere.

And that began the Kendeda Fund’s search for a partner. I think that Georgia Tech became the logical choice, and ultimately we formed a partnership because building to this audacious building standard’s not the first time Georgia Tech has done something that’s groundbreaking when it comes to sustainability. For the 1996 Olympics we had a solar natatorium. We had a really large solar system on that building which my understanding has remained the world’s largest rooftop solar system for a long time.

So from the Kendeda Fund’s perspective, they really want this building to be a catalyst for change across the Southeast. So that’s what The Kendeda Building is, and I really haven’t gone into the Living Building Challenge, and I’ll do that in a moment.

The Living Building Challenge, Version 3.1

BILL YATES: Yeah. So the Living Building Challenge, to me, when I just do a quick, you know, just go barely below the surface, it’s like LEED certification on steroids.

SHAN ARORA: Yeah.

BILL YATES: Tell us more details, so how do you reach the certification of Living Building Challenge?

SHAN ARORA: Well, it’s great that you mention LEED because green certification programs like LEED, especially LEED, allowed for this “LEED on steroids” to even come into place. Green certification programs have moved the market in lots of sectors in this country, especially commercial office. If you’re not building to LEED, you might as well not build.

But there was a group of architects that asked the question, is it good enough to have green buildings that do less harm to the environment? In a resource-constrained world, we need buildings to do more, to give back to the environment. We spend 90 percent of our time indoors, so the buildings have to encourage health and happiness in their occupants. So they asked the question, if you could start with a blank slate and design a building to give back more than it takes, what would “good” look like?

And so that was the Living Building Challenge, and this organization is now called the International Living Future Institute. They looked across nature and said, is there an example in nature of something that gives back more than it takes? And they came up with the flower. A flower shows up, goes away, having left almost no trace of it ever having been here except for the seeds, the life that a flower gives. So going with the flower metaphor, the performance areas of the Living Building Challenge are called “Petals.” In this iteration of the Living Building Challenge there’s seven Petals. Those Petals are place, water, energy, health and happiness, materials, equity, and beauty, so those are the conceptual framework, the seven Petals.

And in order to be a fully certified Living Building, you have to hit the requirements that are across all seven Petals. You can’t pick and choose. Which makes it different from other green building certification programs, so you’ve got to do all 20 things across those seven Petals. Most of it occurs during the design and construction process. But unlike other green certification programs, once you build it and prove that you build it to a certain standard, you don’t get the plaque. You have to prove performance, because the two Imperatives that people know the most about, is net positive energy and net positive water.

Those two things can only be proven once the building is fully occupied, and we’ve got to perform to that standard over the course of 12 months, that makes this thing really challenging. When you’ve got 20 things that have to be done across seven performance areas, every one thing you do better satisfy more than one of those 20 requirements. Otherwise, it’s just going to be untenable.

Red List Materials

SHAN ARORA: What we’re looking at right now is a sign for something that’s called the “Red List.” The Red List is a requirement that is baked into the materials Petal, which is the most difficult Petal of the seven Living Building Challenge petals. And so what the Red List seeks to do is eliminate 22 worst-in-class chemicals and materials known to cause harm to human health in the natural environment. And the requirement is no Red List materials in any permanent part of a building. Asterisk. Because you start getting into exceptions, these things are everywhere. They’re things like BPA. Asbestos and lead thankfully are no longer everywhere, but PVC, flame retardants, Chromium-6, phthalates, they’re everywhere.

So what we have done in this process is go through a procedure to vet every single item that has gone into this building, every permanent item. And so it makes a lot of sense, we spend 90 percent of our time indoors. We know what we eat. We know the ingredients of what we put into our body. But aren’t we putting the materials that we sit on, the air that we breathe into our bodies, and we have no idea what’s in it.

With this project, we told a subcontractor we can’t use PVC. And so they were forced to find an alternative, and it turns out they liked the alternative better. It’s Red List compliant, and it actually works better for them.

Ceiling Construction

BILL YATES: Let’s take a listen to John as he describes the ceiling and what went into constructing it and some of the decisions that were made.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: One of the great stories about this building is the net positive waste requirement. As Shan mentioned, during construction, you know, we had to recycle as much as possible, so they recycled 99 percent of the construction debris from the site. But in order to get net positive we had to look at ways to use salvaged materials, which to me that ended up being the big surprise on this project. It was something that, you know, we’ve done a little bit of before, but not on this scale.

We’re in the lobby of the building, and we’re looking up at the underside of the roof, which is a wood structure, and you can see a combination of 2×4’s and 2×6’s when you look up at this deck. The 2×6’s, those are the structural members, but not every member needs to be structural, according to the code, so there are 2×4’s spaced between the 2×6’s. Okay, so they’re alternating 2×4’s and 2×6’s. The 2×4’s are salvaged wood from movie sets, and that helped us tremendously in terms of showing that you can use salvage products, avoid putting things in landfills, and turn it into something beautiful. So it’s one of those examples of something that serves multiple functions.

And there’s another good story behind that. In order to build this deck, the contractor, Skanska, went out and sought help from Georgia Works!, which is a nonprofit that focuses on helping people get back on their feet. They may have had addiction issues, or criminal records, and they’re trying to get their life on track, and so they hired a few folks from that program and built these decks. And they built 489 of these panels, and so what’s happened is that some of those folks have gone on to careers in construction.

So Living Building Challenge is part of the Equity Petal, requires us to seek out opportunities to help others, and that was a prime example of how that happened on this project, and it’s a great story. And I got to meet one of the guys, and you know, he said that he had not worked a permanent job or full-time job since 9/11. So it was just last year that he finally got his life completely on track and was able to get a career.

The Staircase Story

SHAN ARORA: So this is a staircase that’s leading us from the main entrance up to the second floor. The wood that is used to construct this staircase was part of the original construction of Tech Tower, the most iconic building on campus. This wood, some of it began its life, the trees began their life in the 1600s. They were cut down in the late 1880s to build Tech Tower, during a renovation, these pieces of wood had to be removed. Normally they would have been mulched or thrown away, again, because we knew this building was going to be built, we salvaged it. And now we’ve got alumni that come just to see this staircase because it’s history.

Another piece of history are all of these countertops that you see. So what we’re looking at is what we call “live edge countertops and benches.” Those are made from trees that fell down naturally on campus. So these beautiful oak trees that we have here fell down, and we turned that into furniture that really tells a powerful story and brings a connection back to place –And remember, the first Petal is the Place Petal, and another Petal is Beauty. People are really attached to place, and people like beautiful buildings.

BILL YATES: I noticed when I first walked in the building, the first thing I smelled was wood. And I love that, you know being able to walk into a building that’s this useful and you smell the fresh resource of wood right off the bat.

Managing Triple Constraint Requirements

BILL YATES: Listening to the description of how all the thought that had to go into this building just blows me away as a project manager, and so fortunately we’ve got John here at the table with us who’s seen this thing from birth to delivery.

SHAN ARORA: Conception.

BILL YATES: Conception, even, so there you go, that’s right. That’s a great point. But John, you know, the classic triple constraint comes to mind. When I was even researching this building I was thinking about most project managers are thinking scope, schedule, and budget. Now, you know, you add to that quality and safety and other features, as well, but those big three. And I’m thinking, you know, in the terms of this Kendeda Building and this project, scope had to be the most difficult thing for you, the requirements, because you’ve got, these Petals and the depth of making sure that every Petal was fully satisfied. So I think project managers would say, John, you must have been overwhelmed trying to manage these requirements. How did you do that?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Well, first of all, it comes with selecting the right team, so that’s a key piece of this. One of the things that we did that was a little bit different than our selection process on previous projects is that we had an ideas competition. We went through a process where we publicly advertised the RFQs, Requests for Qualifications, I think we got about 17 or so responses. We shortlisted down to three teams, and we took that opportunity to do an ideas competition over a three-month period. What that did was that not only demonstrated their qualifications, but it also allowed us as, you know, stakeholders in this process and owners to get educated about what the Living Building Challenge is, what it takes to do it.

So one of the other things that we did in the qualifications reviews – we wanted to grow the local expertise. There weren’t any teams locally that had successfully completed a Living Building Challenge at that point, as of 2015. Lord Aeck Sargent had some work on a project in the islands, but it wasn’t built. So we required that the local team, the lead, team up with other design teams that had Living Building Challenge experience. So the three different shortlisted teams all had members of their team that had gone through this process previously, and that was critical. The learning curve on the Living Building Challenge was pretty significant, so you don’t want to do that with someone that had never done it before.

Understanding the Project: John’s Story

BILL YATES: You know, so one thing, John, just is jumping out at me. I have been in situations before, I’m managing a project, and there’s something technically in it that I don’t know, I haven’t been exposed to before. I haven’t had to go into it before, did you face that with this? And so did you have to, like, go to school on these qualifications for building to that degree? How did you – did you fake it?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Well, this is actually a coincidence, so I’ll give you a little bit of background. So I decided to go back and get a Master’s degree in Facilities Administration, and I was actually taking a class when I heard about the Living Building Challenge project may happen here on campus. Coincidentally, that class had a group project in which we had to study green certification systems.

BILL YATES: Ah, okay.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: I selected the Living Building Challenge. So my group did that, and when I read that book, I was floored. I’m like, how is it possible to do this? When you read it, it’s pretty intimidating.

BILL YATES: It’s going to be daunting.

SHAN ARORA: Oh, yeah.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Yeah, so it’s kind of – it’s got, you know, net positive requirements, and I had a hard time understanding how can you possibly achieve that. And then it had these kind of socioeconomic components, equity and that kind of stuff, which – so there’s the quantitative, and there’s the qualitative, and beauty, and how do you – how do you measure that?

BILL YATES: How do you measure that?

Team Selection Process

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Yeah. You know, so while I was able to get to dabble in it, I still wasn’t familiar enough as to know how to execute something like that. So relevant experience of the team members that we were selecting was critical. That was a driver in terms of the process. So when we went through the selection process, one of the other things we did was we had two touch points with each of the teams. So there were three teams, we had six visits to their offices as they were working, we were like flies on the wall. We could not give them direction so that we could keep a level playing field between all the different competitors for this project.

So we basically stood there and kept our lips, shut and watched them work. And so we wanted to see the interplay between the different disciplines within that group.

BILL YATES: Oh, yeah, sure. Engineer, architect, all that.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Exactly.

BILL YATES: I can’t – I’ve never heard of a company doing that. How open were the bidders to you guys doing this, showing up?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Well, they didn’t have any choice.

BILL YATES: Okay.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: But they knew it going into it that we were going to do this, we made that clear, but it served multiple purposes. So it helped us to see how integrated their team was, and all three teams were phenomenal, frankly. I mean, we had a hard decision to make at the end, one of the things we wanted to see was the chemistry of the teams, as well. So is the architect standing up there saying this is my vision, and this is what we’re going to do, and you just need to make this work? Or was it the engineer, elbow to elbow with the architect, saying, you know, think about this idea. And so as you look out the window in the room that we’re in, you’ll see, the canopy structure has a very thin column with these outriggers and tension cables; right?

BILL YATES: Yes.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Or tension rods. Well, that idea was created during that conceptual phase where the structural engineer said, okay, we want to reduce the carbon footprint on this building, so how can I build this canopy using the least amount of steel possible? So he did moment diagrams and figured out where he needed to put these outriggers, and, and so we’ve got a very thin column holding up like a 40-foot canopy. And that was an idea that I think turned out, obviously by an engineer, designed by an engineer, turned out to be one of the most iconic components of the building.

BILL YATES: Yes.

SHAN ARORA: Yeah.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: And it’s beautiful, so that’s the kind of integration that we were looking for, and that competition allowed us to see that in action.

A Heavily Populated Certified Living Building

SHAN ARORA: The Living Building Challenge is only 23 certified Living Buildings.

BILL YATES: Twenty-three…

SHAN ARORA: Fully certified, ballpark.

BILL YATES: Like in Georgia? In the U.S.? In the world?

SHAN ARORA: Oh, no, in the world.

BILL YATES: In the world. Worldwide, 23.

SHAN ARORA: Worldwide, with most of them being in the Pacific Northwest or the Northeast. There’s a Living Building Challenge v2.0 Welcome Center in Chesapeake Bay in Virginia. And there’s a smaller project on the Gulf in Alabama that’s also seeking v3.1.

BILL YATES: We just walked by and saw a classroom with hundreds of students going into it for probably a chemistry class, you know, first year.

SHAN ARORA: Yeah, about 170 students for a chemistry class.

BILL YATES: Yeah. So you have hundreds of people in and out of this building on a daily basis.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Exactly. And that’s one of the distinguishing factors between this project and a lot of the other Living Building Challenge projects is that I don’t think anybody rivals us in terms of the population that goes in and out of the doors, and so – not even close. And so that’s a major consideration, and during the design process we were always looking at that and thinking about, you know, how can we reduce the heat load on the building? We have a canopy that, you know, helps to shade the roof.

BILL YATES: Big umbrella, yup.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: But we also have operable windows, which is part of the ventilation system for the building on appropriate days. We have weather stations that tell us when it’s appropriate to open the windows, but, you know, how do we drive down the mechanical system usage? And so, there were a lot of strategies that were driven by the program of this building, and it made such a difference, I think, at the end of the day. So this is the proof of concept that you can build a heavily populated building in the Southeast – a hot, humid climate.

BILL YATES: Right.

Continuing Education

WENDY GROUNDS: What I love is that it’s been done here in a university on a campus where there are students, and these are our designers of the future and the engineers of the future. And so they’re getting to experience this and, you know, walk through a building, have classes in a building that’s going to make an impact on them, and take it forwards. So kudos to that.

JOHN DU CONGÉ: And that’s a great point, and so I’ll point out one other thing that directly relates to what you’re saying in that. So we have four classlabs in this building, and talking to the different colleges within the campus about who’s going to go in this building, College of Sciences said, “We’d like to go in there.” We said, “Well, so what you’re going to have to do is you’re going to have to agree to a water budget and an energy budget within your classroom.” So we’re taking the pedagogy and changing that in order to fit a more sustainable approach. And so that sticks with students, and that helps them to think before they turn on the faucet, you know, and how do they dispose of things, and when they’re turning on lights and all of that other stuff.

SHAN ARORA: So we’re asking people to get comfortable with a different type of toilet, you know, we’re asking people to be very mindful of what they do on a daily basis. And the building allows us to do it in a way that’s not – I don’t think it shames people because of what it’s saying is we’ve taken it here. All we’re asking you is to adjust your behavior just a smidge. And hopefully that becomes habit, and the students leave this building with a changed habit, with changed expectations, because these students are going to be the future customers of buildings. They’re going to be the future owners of buildings, and so we need to set a new expectation of what they expect in the market.

Podcasting in the Restroom

WENDY GROUNDS: You guys talked about waste disposal, and so we took a tour of the toilets and the composting toilets and how that works. We went down into the basement, so let’s go back and have a listen to that.

SHAN ARORA: We have a lot of potty talk in The Kendeda Building, and there’s no tour of The Kendeda Building is complete without a whole bunch of people walking out of this particular restroom, so hold on.

[Knocking] Facilities. Hello? We’re about to podcast in here. Okay. I can say this is the first podcast that I’ve had in this bathroom; right?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Yeah.

SHAN ARORA: First podcast, yeah.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: It is the first podcast.

BILL YATES: Nice.

SHAN ARORA: I want to point out the wall. So the slate tile has been reclaimed from the roof of Georgia Tech’s Alumni House on North Avenue. The slate roof was put into place in the 1920s, was perfectly fine, there was a water leak, and so the slate roof had to be taken off, and normally that would have been thrown away.

But because Georgia Tech knew that this Living Building was going to be constructed, and one of the requirements is to be net positive during the construction process and to divert waste from the landfill, we kind of got in front of this stuff getting thrown away and repurposed that slate to be used on this wall. So the slate got initially put onto a roof in the 1920s and would have been thrown away, and now it’s in The Kendeda Building and will outlive all of us. Which begs the question: Why are we throwing away perfectly good stuff? Right.

But if you hear the hum, the hum in the background is a very unusual and unique toilet, and this is really a story of how going to the restroom in The Kendeda Building is part of the global climate solution. In Georgia, the vast majority of our electricity is produced by burning fossil fuel, so electricity has got a lot of carbon pollution baked into it. Why are we going to the bathroom in water that’s, A, drinkable, and, B, has that much carbon pollution baked into it? So what we’ve done in The Kendeda Building is use rainwater for a foam flush toilet that only takes about a tablespoon per foam flush. And then we treat that sewage onsite.

Net Positive Water Consumption in the Bathroom

JOHN DUCONGÉ: One of the things that occurred during the design phase was just an analysis of water consumption and how can we cut that down and just in general, so you know, being net positive water we had to do a pretty significant analysis on that. And Living Building Challenge requires us to either use a black water system or a composting system, so we did the side-by-side comparison, and the composting system was by far the more economical approach. So there was a little bit of training, I think, the first few weeks that had to happen.

But if you look, we’re in the restroom, and now we’re looking into the stall, so one of the things that happens that’s different about this is that you don’t touch anything. You step into the stall, and automatically the toilet starts to foam up, and the reason for that is it’s priming the bowl for use. Okay, so all you have to do is go in, the foam starts up, you hear that hum, and the foam is going, and now you go in and you use the restroom, and then you leave. You walk out. That’s all you have to do. And so the rest of the foam helps all the waste matter to go down into composting bins which are located in the basement. And we’ll take a look at that in a minute.

WENDY GROUNDS: I have to tell you there’s no icky toilet smell here. This is a beautiful clean room. And I’m really impressed. This is quite phenomenal.

Turning Waste into an Asset

SHAN ARORA: On any given tour we do spend a lot of time talking about what happens to things that we throw away, that we get away with. So when we talk about waste, oh, just throw it away, where’s “away”? Where does your – when you go to the bathroom, where does that stuff go? Where does the icky stuff go? It goes away. There is no “away.” So we need to do away with this notion that we throw things away, and things go away. We need to understand it all stays on this planet, and so we need to manage our waste ourselves.

And so in some cases what we think is waste is actually an asset because what we do with it turns it into waste. If we thought about it differently, it would be an asset. So when you go to the restroom here, we don’t connect to the sewer, a 37,000-square-foot building with six restrooms does not connect to the sewer. We take that waste and turn it into an asset, so it turns into compost.

Rainwater normally, in a normal building, would be storm water runoff. We capture 41 percent of that rainfall and turn it into the water that we then use in our toilets and in our sinks, so what would be a problem ends up being an asset. So for project managers thinking about any type of project, how do you take a problem and think of it differently and turn it into a solution?

Podcasting in the Basement

JOHN DUCONGÉ: So we’re in the basement now, and we’re looking at the real working machinery of this building, and one of the things we’re looking at right now are the tanks for the water system. And so we have a condensate tank which captures all the condensate from the mechanical systems, and that condensate water is pumped to the irrigation system outside. So we use that to water the plants.

And then the other part of this is the potable water system, so we’re looking at a concrete wall straight ahead, on the other side of that concrete wall is the potable water cistern. So that’s a 50,000-gallon cistern that we capture water from the roof, and it channels through pipes down into the cistern, and then it goes through this filtration system that we’re looking at where it has carbon filters, and there’s also UV to get rid of the biological stuff. And then it goes from there into what we call “holding tanks.” So we have day tanks to provide us a five-day supply in case the system’s down and we have to operational repairs or something like that. We’re in the process now of working with the EPD to get a permit to operate this, so we’re currently on municipal water until we get that permit.

SHAN ARORA: Here we are, so this is where almost all of our tours end, in front of six green buckets, like giant buckets, and then there are two 1,000-gallon tanks. In an interview that John and I had for NPR, I referred to this as “We built outhouses inside.” And so oftentimes people say, “Oh, you guys have that super high-tech building.” Well, this is a pitchfork. So it’s not that high-tech because some of the stuff we do here is positively low-tech, this being one of them. The entire composting toilet system, there is technology and engineering associated with it, but the way that we break down that waste material, we are leveraging nature. That’s what nature does on a daily basis.

So what I’m doing right now, and everyone’s laughing, is I’m slowly leaning towards the lid of one of the green boxes, and I often stop and do this because there’s this anticipation. People are like, what are we going to see? What are we going to smell? And so I just, you know, I prolong the process. I prolong the pain, and what I’m about to do is the most anticlimactic thing on this tour because I open this lid and everyone goes, oh. That’s it.

WENDY GROUNDS: I want to assure you that I’m not smelling what you think I’d be smelling in the basement.

SHAN ARORA: What you see here is pine shavings, pine shavings is the bulk that is needed to help break down the biosolids. Most of the biosolids is in fact liquid. So what happens is, deposits end up here at the top of the bin, the decomposition process, the natural process takes time. Most of what’s broken down is liquid, so this sump pump right here takes the liquid and puts it into one of these two 1,000-gallon tanks.

So the actual solid that’s left is bulked up with the pine shavings, and it’s going to take years and years to accumulate, the only local example we have that we know of is Southface Energy Institute. They’ve had a smaller version of this same exact system for 10 years, and so just now their solid is getting to the point where they’re going to have to move it out. What we have to move out more frequently is the liquid, so what we’re looking at right now are two 1,000-gallon tanks.

This gets back to the climate solution, so the end product of this is fertilizer. So not only do we save a lot of electricity – by using natural processes in-house, at the end of the process, instead of having a waste product, we have a beneficial product. So what we’re doing with this particular what we call “compost tea,” or leachate, is we’re taking it to Cartersville, where the waste processing will strip it of its nutrients.

In other parts of the country, the authorities allow for this to be sprayed in the woods as land application. They allow it to be sprayed in parts where humans aren’t going to be walking or food’s not grown. And nature just breaks it down in a couple of days.

Project Surprises

BILL YATES: John, one of the questions I’ve got to ask you as the project manager on this baby is what surprises – what were your biggest surprises?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: The pleasant surprise for me is the use of salvaged materials and how that can really dramatically change, not only the look of a building, but it changed our costs actually, quite frankly. So from a project manager’s standpoint, it helped the budget when we look at the use of salvaged materials in the floor structure system, for example, the 2×6’s are structural wood, and then the salvaged wood is the 2×4’s. Turned out to be one of the most beautiful aspects of the project.

BILL YATES: Yes.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: And so that kind of creativity demonstrated to me that we can take this to a new level in future buildings. That is one of those things that I think I could never have anticipated early on, before I did this kind of a project

So I’ll tell you one of the other things that surprised me, and one of the recommendations I would make is to keep things simple. We have four, and this is the name of the company, Big Ass Fans in this building, so there are two in the…

BILL YATES: I’ve seen them, and they are.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Yeah, they are.

SHAN ARORA: They are.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: There are two in the lobby, and there are two in the auditorium, so we had a significant event early on, once we opened the building, probably a couple hundred people or more. So our IT guy was in the auditorium trying to get all of that squared away, and the thing about fans in a room like that is that, if you turn up the fan speed too high, it blows the screen, the projection screen.

BILL YATES: Oh, sure, yeah.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: It makes it move.

BILL YATES: A presenter’s nightmare.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Exactly, so he was in there trying to get the fan speed down in order to stop the screens from moving. And so he came to me and said, “John, every time I turn down the fan speed, it ramps back up for some reason. I don’t know what’s happening.”

SHAN ARORA: I remember this.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: So, you know, so I went, I said, well, let me find the contractor who was actually onsite with us for this event, and I said, “I’m going ask him to take a look at it.” But before I could even get to the contractor, the Area Six manager, Marlon, was in the atrium, and he said it was getting kind of warm; you know? So he kept turning, he said – and he came to me and said, “Every time I turn the fans up, you know, somebody keeps turning it down.”

BILL YATES: Somebody turns them down.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: “So I don’t know what’s happening,” and then it was like, okay, now I get it. But what happened is all four fans are on Bluetooth.

BILL YATES: Okay.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: And they were on the same frequency, so, you know, so they were competing against each other. So if we had just put in wired, you know, just simple old-school wired system, we wouldn’t have had that issue.

BILL YATES: Right, keep it simple.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: So keep it simple.

BILL YATES: The way you capture – so you mentioned you captured 41 percent of rainwater from this canopy.

SHAN ARORA: And the roof, yeah.

BILL YATES: And the roof.

SHAN ARORA: The combined, yeah.

BILL YATES: That’s fascinating. It’s simple, but it’s brilliant; right?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: The story behind that is, the photovoltaics are our rainwater harvesting strategy as well as, providing the electricity for the building. In addition to that it’s shading the roof and providing shade over our outdoor kind of gathering spaces on both the roof garden, as well as down on the ground level, and so…

SHAN ARORA: And they’re beautiful.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: And they’re beautiful.

BILL YATES: Yeah, yeah.

The Cost of Sustainable Design

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Like Shan said, everything has to do multiple things, and so, one of the things that I think is a misunderstanding about sustainable design is that it’s expensive. I think that you can pick pieces and say, yes, that’s costly, but when you look at the overall kind of approach, it really does pay off at the end of the day. So just think of how our heating bills and cooling bills are lowered as a result of some of these strategies. So having a canopy, you know, that hovers over the building, cools the roof or reduces the heat load on the roof in those hot summer months, is tremendous. But that doesn’t get factored in. People don’t really think long term.

BILL YATES: Right.

SHAN ARORA: A mentor of mine who I respect a lot, who knows a lot about the real estate industry and buildings, said to me, “If you’re not building to regenerative standards, you’re building to obsolescence.” So what that means is, if you think the reality of the economy, of the climate today is going to stay the same, all right, that’s the bet you’re making. But if you want to buy yourself insurance, build regenerative because you are future-proofing your building. You’re baking in insurance.

Another thing I used to say to people when I was doing clean energy advocacy is, “Raise your hand if you think the electricity rate or the water rate is ever going to go down in the future.” No one raises their hand. So if the entire market knows something is going to happen, if you build to regenerative standards, you’re basically buying insurance, that’s economic resilience. If you don’t build regenerative, you’re building to obsolescence.

Looking Back on the Project

WENDY GROUNDS: This was from conception that you started with this, and so if you’re looking at what your vision was and what you’re looking at today, has it exceeded your expectations? How do you feel like, kind of as the dad, looking back on this now?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Great question. Yes, it did exceed my expectations, and I’m so incredibly proud of the outcome here because, you know, it’s one thing to see a concept. And you have your own vision, I mean, they do little sketchy kind of renderings and whatnot, and so you kind of imagine what that could be. But then it turned out to be so much better than that.

And part of that is just the stories that we told you already behind that, having been through that process, and so what it took to get here is part of, kind of, that has value to me. But I think it brings value to everybody that hears about this building. Like Shan was saying, diverting things from landfills and making it into something beautiful, so I think that’s just one of those intangible kind of things that, if you just walk in the building, you won’t know that. But if you hear that story, I think it’ll resonate.

One thing that is amazing, though, is that when we did the ideas competition, so you know, they all had their renderings of the buildings and whatnot. And so if you look at the rendering of this building from the outside, it looks just like what this turned out to be, you never expect that to happen. Usually you value engineer things to the point where, you know…

SHAN ARORA: Even down to the trees.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Exactly.

SHAN ARORA: Even those two trees.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: It turned out that this building is probably the most like any conceptual drawing I’ve ever seen.

BILL YATES: How about that, yeah.

WENDY GROUNDS: Love that.

BILL YATES: John so looking back on the project, if you could go back in time, is there anything you would do differently than you did? Any place you’d want to have a redo?

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Shan’s looking at me like, sure, I can give you some ideas. Well, so I think going back to keeping some things simple, trying to simplify certain things. I think we were relying on technology a lot, but, there’s pluses and minuses to that.

BILL YATES: This is Georgia Tech.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: It is Georgia Tech, that’s true, and so I think that at the end of the day, once the dust settles, all of those things will get worked out, and they’ll function well. But, to the degree that you can, try to make things as straightforward as you can, that helps us, I think, over the long term. But in terms of the experience on this project, I think we selected a great team. So we had team members that were dedicated.

And so I would say that was one of the other things that was critical in the selection process was that, on a project like this, we selected a team that had sustainable design in their DNA. It was evident. And it takes that to do this.

WENDY GROUNDS: Well, guys, thank you so much, this has been an exciting morning for us, our first podcast on the road. So that’s been really fun.

BILL YATES: Yeah.

WENDY GROUNDS: And we’ve loved the tour, we’ve also loved hearing your passion. Both of you have really given us a lot to think about, and I think our audience, as well, and so I hope that people take it to heart and start thinking about how they can help the environment, and things that we can all be doing, choices we can make.

Now, we have two mugs for you guys, so I’m not sure if they have any of the Red…

BILL YATES: The Red List?

WENDY GROUNDS: Yeah, Red List.

SHAN ARORA: Thank you.

WENDY GROUNDS: But they are from Manage This to say thank you so much for being our guests, and we hope you have many days of…

JOHN DUCONGÉ: All right.

SHAN ARORA: Thank you.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Well, we appreciate that.

SHAN ARORA: Thank you very much.

BILL YATES: Use them and continue to use them and continue to use them.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: We’ll drink our sustainable coffee in that.

BILL YATES: We really do appreciate it, and it’s so impressive to see the building today and be able to walk through with you guys and see firsthand what you’re describing and to feel your passion for this project.

JOHN DUCONGÉ: Yeah, so I would invite, your listeners to come out and take a tour, they can sign up online. You can just…

SHAN ARORA: Livingbuilding.gatech.edu, and just click onto the Tours button.

WENDY GROUNDS: Thank you so much.

Closing

Hey folks, before we go, if you have a look at pm4change.org, you’ll find out about the project management day of service, so it’s an excellent opportunity that brings together local project managers and non-profits. Kendall Lott is the executive director of project management day of service, and he also has an excellent podcast called PMPoint of View. Go and take a listen.

Kendall also mentioned another great podcast by Laura Barnard called PMO strategies podcast, so they recorded episode 34 called the impossible PMO. It’s also worth a listen for a meaningful discussion relating to forming a team to do volunteerism, I will put the link in this episode transcript if you would like to take a look at these podcasts,

Just a reminder to our listeners about the free PDUs, you just earned for listening to this podcast. So to claim them, go to velociteach.com click where it says Manage This podcast at the top of the page, and you’ll see a tab that says claim PDUs. Click right there, and you’ll be guided through the steps, until next time, keep calm and manage this.

Leave a Reply